Sonata para guitarra by Antonio José (1902-1936). This is one of the great modern Spanish works for guitar and simply one of the most significant long form sonata works for the instrument. This was José’s only work for guitar, composed in 1933. Maurice Ravel apparently said of Antonio José: “He will become the Spanish composer of our century”. Movements of the sonata are: I Allegro moderato; II Minueto; III Pavana triste; IV Final. More info on the piece below.

Recommended Sheet Music

Sonata para guitarra by José (Berben)

Recommended Recording

20th Century Guitar Sonatas by Michael Kolk

Recommended Video Performances

Michael Kolk on YouTube (1st Movement)

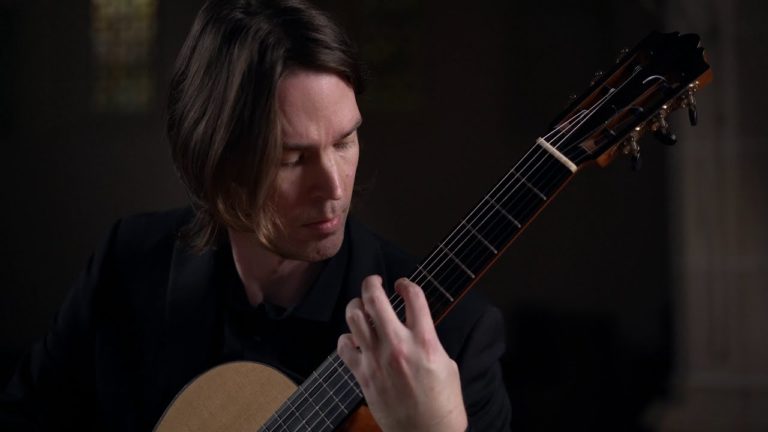

Goran Krivokapić on YouTube (Complete)

There is a great write up on the work by Graham Wade via this Naxos album:

Antonio José (1902–1936) was praised by Maurice Ravel as a composer who would ‘become the greatest Spanish musician of our century’. But José’s arrest and execution near his home city of Burgos in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War cast his music into a subsequent obscurity which has only recently been remedied. A monograph about his life and work has been published by the municipality of Burgos.

Considerable interest was aroused by the discovery in the late 1980s of the Sonata, which Antonio José finished on 23 August 1933. One movement was given its premiere in Burgos by Regino Sáinz de la Maza in November 1934. Sonata offers further perspectives on the expansion of the guitar repertoire during the early 20th-century Spanish musical renaissance. The work established Antonio José’s reputation beside those of his distinguished contemporaries who respected the guitar as an expressive medium. José’s Sonata is a composition requiring virtuosity as well as emotional depth and insight.

It can be observed with historical hindsight that José’s Sonata is a remarkably original and inventive work, written in a period of very few precedents for guitar in this genre. By 1933 Moreno Torroba, Ponce and Turina had indeed presented various pieces in sonata form to Andrés Segovia, but it is by no means certain that José was acquainted with these compositions.

The first movement contrasts the lively lyricism of the opening statements with meditative slow chords and answering arpeggio patterns. This leads to a passage characterised by urgent pedal notes sustaining a short burst of three-part chords before the return of the opening section and a modified recapitulation. In these final pages, the previous musical substance is taken through various modulations before concluding with a resounding chord of E major.

The Minueto retains the 3/4 metre of its traditional 18thcentury predecessors, but otherwise assumes an entirely 20th-century vocabulary. Though the essence of its opening theme is straightforward, its harmonic basis is complex, leading to a rainbow of modulations through diverse keys and labyrinthine sequences. Similarly Pavana triste, written in 3/2 time, brings a new language to an ancient dance form. At first dotted rhythms suggest a certain lightness of atmosphere but the predominant mood of the movement turns out to be melancholic rather than lyrical. Once again, intricate harmonic progressions lift this dance to new expressive heights reminiscent of Rodrigo’s use of traditional musical structures to create fresh and meaningful vehicles for modern music.

Final begins with strummed chords characteristic of the Spanish guitar. Their function is not to provide Andalusian associations but to establish part of a compelling framework for statements of the first movement presented in modified rondo form. This structure supplies a powerful means of presenting familiar material from new perspectives while achieving a unifying effect between the first and last movements. After much harmonic divagation, the work ends decisively on the chord of E major, one of the most convenient and appropriate keys in keeping with the guitar’s usual tuning.