Introduction

French tablature was a common tablature style for lute and early guitar in the Renaissance and Baroque period, in particular, around England and France. Early music enthusiasts and professions still use and read French tablature today. Like modern tablature, French tablature uses lines to represent the strings of the guitar. The big difference is that French tablature uses letters to indicate the fret location.

Why Learn French Tablature? There are endless amounts of lute and early guitar music waiting for you to play and arrange for classical guitar. Much of it has never even been played on guitar before. But even if you are not this ambitious, learning to read French tablature is invaluable for checking the accuracy of the editions you use. Editors have to make many changes and decisions when arranging early music for guitar and being able to read the original manuscripts yourself is the only way to check its authenticity and accuracy.

Note: A separate article will soon be made on reading Italian tablature.

Important

Before you read any French tablature, you must know what instrument it was intended for, the tuning of that instrument, and the number of strings/courses. It can also help to know the composer and the geographic location, as well as who might have copied out the manuscript because there is a wide variety of different indications and symbols used. Without these important clues, your music might not make much sense.

Not Always Possible to Play on Guitar – It is not always possible to read selections of French tablature on guitar if the intended instrument is too different in tuning or number of strings. However, much of the Renaissance lute repertoire is both playable and readable on guitar with minimal tuning differences.

Basics

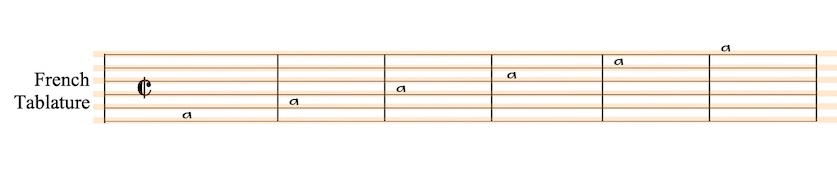

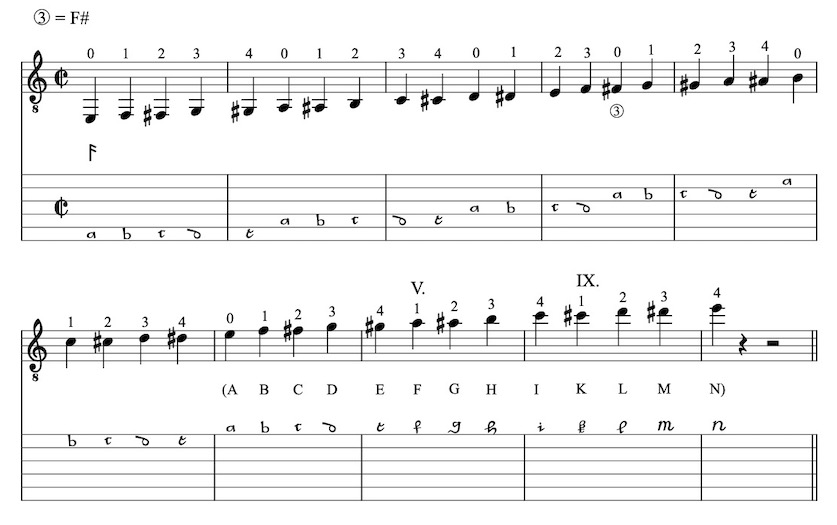

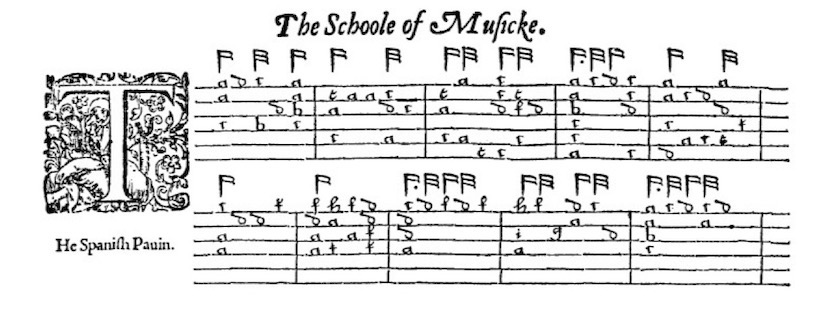

French Tablature Commonly has Five or Six Lines – Tablature for lute often uses six horizontal lines which represent the strings whereas Baroque guitar music can use five lines as the instrument commonly has 5 courses. In the example below, the lowest/bottom line is the lowest pitch bass string on a guitar or 6 course lute. Diapasons (extra bass strings) will covered later in this article.

French tablature uses letters to indicate the fret

- a = open string

- b = 1st fret

- c = 2nd fret

- d = 3rd fret

- e = 4th fret

- etc.

The letters are commonly placed above the line instead of on the line but you’ll see examples of both later on.

Open Strings

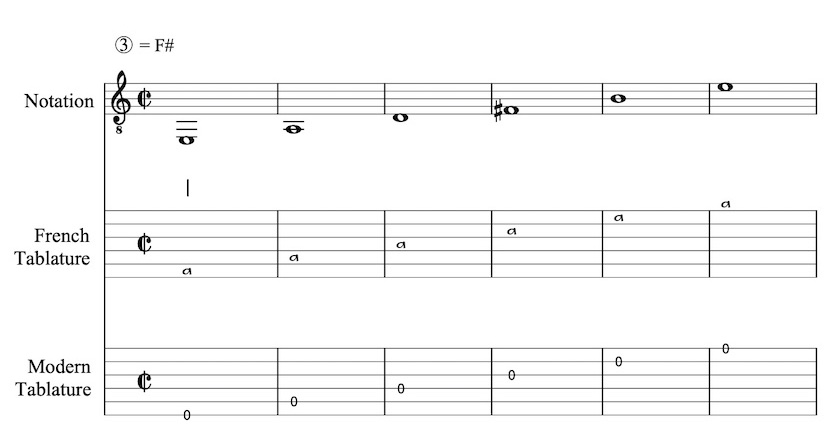

Below is an example including modern notation, French tablature, and modern tablature for the six open strings of a guitar. The notation and tablatures are identical. Diapasons (extra bass strings) will covered later in this article.

Relative Lute Tuning – Most of the examples in this article use the 3rd string tuned down to F sharp (relative lute tuning), which was a common Renaissance lute tuning.

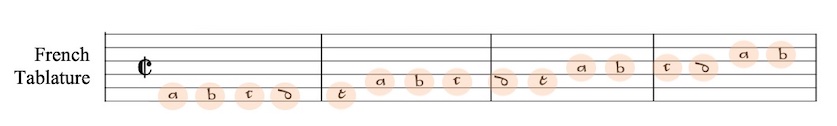

Letters indicate the frets

Below is a chromatic scale in guitar notation and French tablature. All staves are identical. The top staff is regular modern notation, the bottom staff is French tablature. I’ve added letter names above the notes leading up the first string in case you have difficulty reading the font style. Notice that there is no letter j used so i is followed by k.

Below is the same example but comparing modern notation, French tablature, and modern tablature, again in relative lute tuning.

Relative Lute Tuning – Here is video on the relative lute tuning if you’ve never heard of doing that. I don’t emphasize it much in the video but many pieces are not possible to play without tuning down the third string. For example, pieces that utilize an F sharp on the 3rd string while also an open D on the 4th string would not be possible (sometimes you can fret the D but many times not).

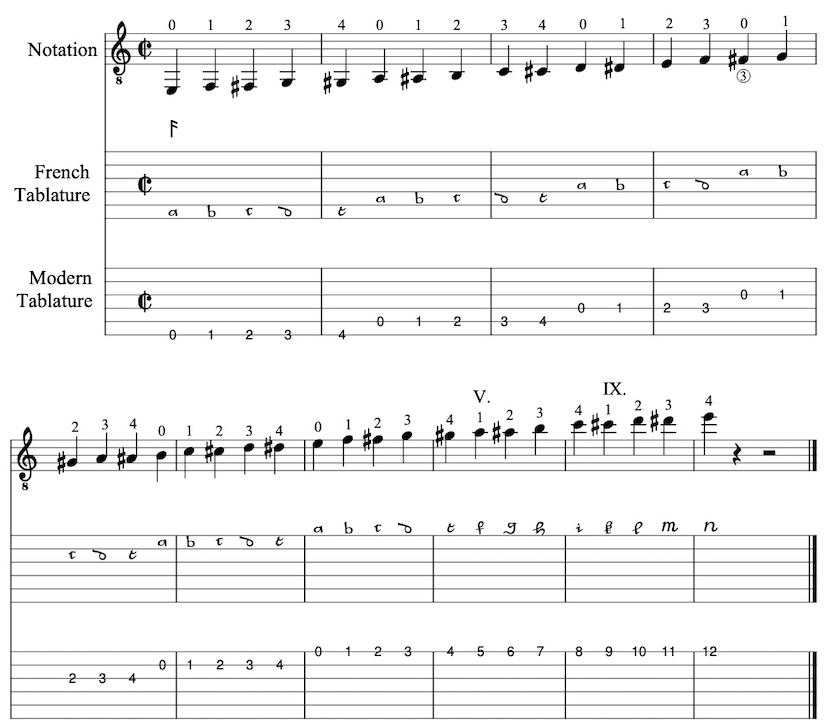

Rhythm Indications

Individual notes do not receive rhythm indications in French tablature. Instead, any change in the overall rhythm is placed above the staff to indicate a change. Once a rhythm is indicated, the performer continues playing that rhythm until another rhythm appears. Just like modern notation, the beats in the measure always add up to the number of beats in the time signature (regardless if an actual time signature is present in the manuscript).

The below French tablature is exactly the same as the guitar notation. Notice how the stem and flag indications are not the same stem/flag rhythms as modern notation. There are a large variety of styles used by composers to indicate rhythms and the symbols can change depending on the composer’s personal preference, the era, and their geographic location. Below I’ve chosen a common rhythmic indication used in French tablature that is easy to read.

Endless Style Variations

There are many variations on the letter font and rhythm indications depending on the composer, era, copyist, or geographic location.

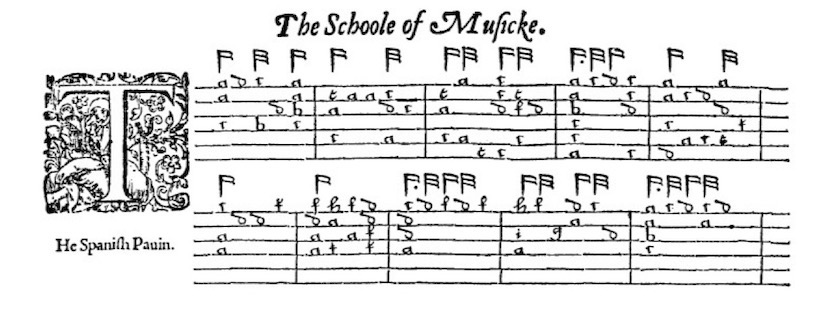

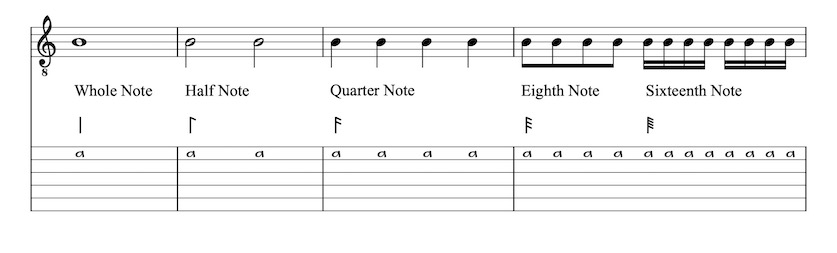

Robinson (English Renaissance Lute) – Below is an example of French tablature from Thomas Robinson’s The Schoole of Musicke (London, 1603). As you can see there is no time signature indicated but there are clearly four quarter notes per measure implying either 4/4 (common time) or 2/2 (cut time). To break it down, the first measure has: two quarter notes, two eighth notes, one quarter note. Also notice that the ‘C’ often looks like a lowercase ‘r’. The ‘E’ also looks different than some people expect. This example is playable on guitar with the 3rd string tuned to F sharp.

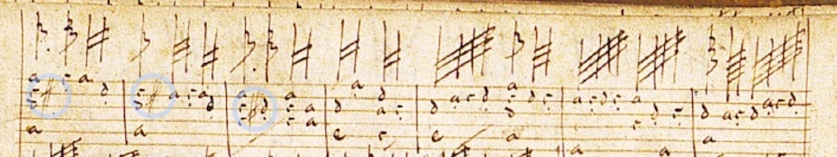

Kellner (German Baroque Lute) – The below example is a Phantasia in A Minor by David Kellner (1670–1748) for 11-course Baroque lute. The letters in this example can be a little less easy to read if the texture gets crowded. Also notice the different style of rhythm indication. This example is not playable on guitar without significant re-tuning and alterations. In these cases the music is often written out and arranged in a key that resembles the use of open strings in a similar way or played in the original key with, often, significant challenges.

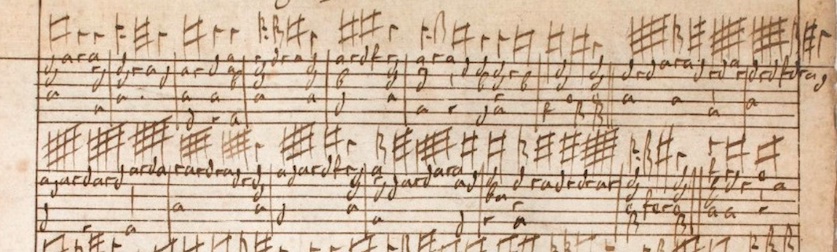

Holmes (English Renaissance Lute) – The below example is from the Mathew Holmes Lute Book (Manuscripts I: Cambridge University Library MS Dd.2.11). The estimated date for the manuscript is (ca.1588-1595) copied probably in Oxford. This is an important source of lute music including some of the works by John Dowland. As you can see we have yet another type of rhythmic notation along with a tight letter format that can sometimes cause ambiguities. This example is playable on guitar with the 3rd string tuned to F sharp.

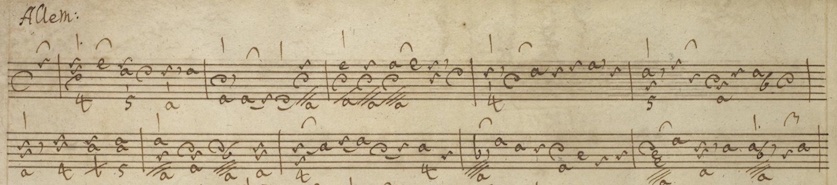

Weiss (German Baroque Lute) – Below is an example of an Allemande by Sylvius Leopold Weiss (1687–1750) via the Dresden Manuscript – WeissSW37.1 à 8 Ms. Dresde D-Dl2841. This example is not playable on guitar without significant re-tuning and alterations.

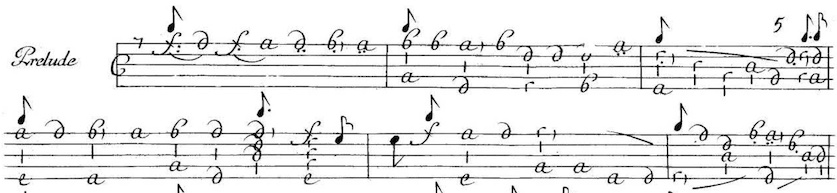

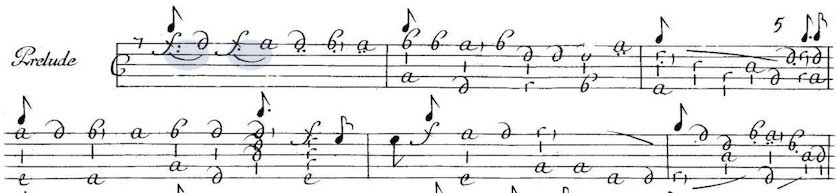

Visée (French Baroque Lute and Baroque Guitar) – The below example is a Prelude by Robert de Visée (c. 1655-1733) for Baroque guitar from his Livre de pièces pour la guitare (Paris, 1686). Notice that this music has only five lines as the instrument has five courses. This example is playable on guitar but requires an awareness of Baroque guitar tuning issues and more explanation of the tablature indications.

Additional Bass Strings

Additional bass strings beyond the 6th string (diapasons) can be indicated in a variety of different ways. One important thing to note is that strings on the lute often have two strings per plucked string which is called a course. That is, when you pluck a single course, you are actually plucking two strings that are close together. With some instruments such as Baroque guitar, a course can be in different octaves which drastically changes the context and makes arranging the tablature for modern guitar much more involved.

Common ways to indicate diapasons (extra strings)

- 7th Course: a,

a, a - 8th Course: /a, /

a, /a, a/ - 9th Course: //a, //

a, //a, a// - 10th Course: ///a, ///

a, ///a, a/// - 11th Course: 4

- 12th Course: 5

- 13th Course: 6

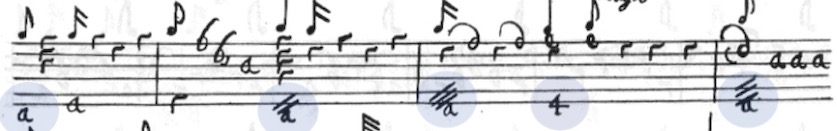

Diapasons Example – The below example is a Phantasia in A Minor by David Kellner (1670–1748) for 11-course Baroque lute. In the third system you can see low bass courses occurring. Also notice the different style of rhythm indication here.

Small Word on Baroque Guitar

As I mentioned at the beginning of the article, before you read any French tablature, you must know what instrument it was intended for, the tuning of that instrument, and the number of strings/courses. With some instruments such as Baroque guitar, a course (two strings close together and plucked as one) can be in different octaves which drastically changes the context of the resulting pitch. Also, in some cases a ‘bass’ string (the one closest to your head when holding the guitar) is actually a higher pitch then the other strings. This means that when you pluck a ‘bass’ string you might actually hear either a high note or both a low and a high pitch if they are in octaves. Therefore, your ‘bass’ string might function as either part of the high voice or low, or both. This can make arranging Baroque guitar on classical guitar a complicated undertaking requiring many alterations. This is one of the primary reasons the music is so under played and arranged.

Transcription and Rhythm: Dowland

Even if the musical texture gets complicated, the rhythmic notation in French tablature stays simple. Editors making arrangements from lute tablature must make editorial decisions on what rhythmic value to assign to each note and how to divide the music into multiple voices (top voice, bass voice, inner voice, etc). This creates a wide amount of variation from one edition to another as editors make different decisions and editorial choices.

Key Takeaway – When transcribing or arranging French tablature into notation, rhythms and voice separation must be chosen for each note by the editor.

Below is the first four bars of Fortune, My Foe by Dowland (from my Grade 6 Repertoire Lessons book). Notice in the first beat of the notation version that I’ve assigned a rhythm to each note in the chord but the French tablature does not.

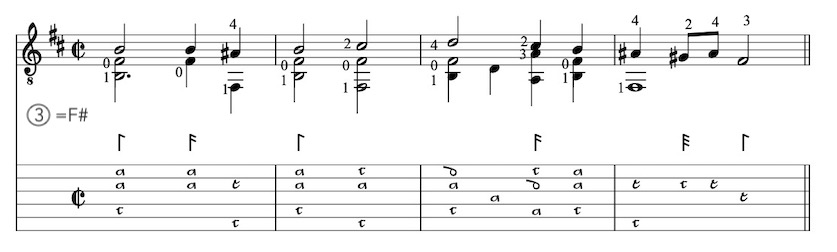

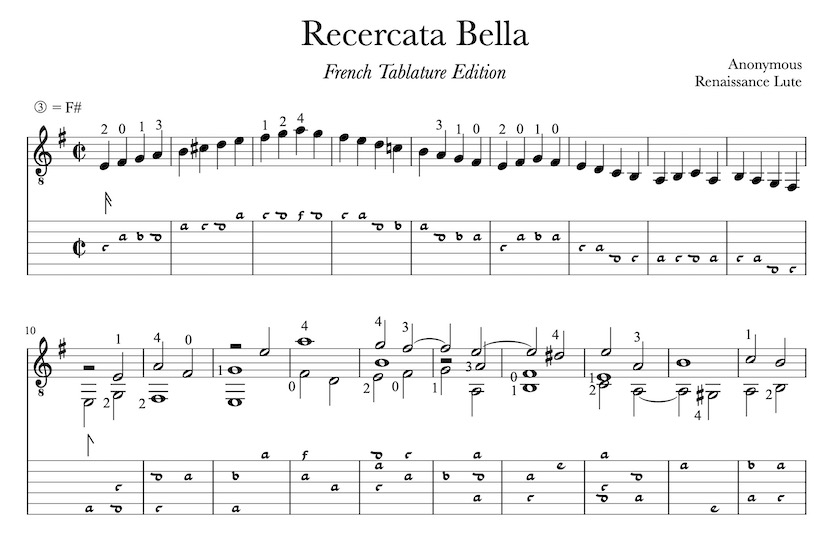

Transcription: Recercata Bella

The below example, Rercercata Bella, an anonymous Renaissance lute work from the Siena Lute Book, is actually from an Italian tablature manuscript but I’ve made a French tablature comparison here. This was a collaboration with Elizabeth Pallett and you can see our sheet music and video here. Notice in the second line where I’ve written the notation out in two and sometimes three voices despite the tablature not giving any indication of separation. I’ve included our videos so you can hear the opening.

Endless Symbols

A vast array of symbols are used in tablature to represent ornamentation, articulation, chords, and other indications. I can’t possibly list them all but here are a few. Keep in mind that all the below symbols may change or mean something different across various composers, copyists, eras, geographic locations.

An example of slurs (highlighted in blue) from Prelude by Robert de Visée (c. 1655-1733) for Baroque guitar from his Livre de pièces pour la guitare (Paris, 1686).

Trill – The below ornament (#) from a work by Dowland in the Folger Shakespeare Library MS.v.a159 could represent an appoggiatura or a shake (trill).

Consistency Problem – One of the main issues with symbols and signs are they change from manuscript to manuscript depending on the composer, copyist, era, and geographic location. Even within collections by the same composer/copyist they can change indications or use them ambiguously. Therefore, direct research into the instrument and composer (etc) is needed to determine the historical accuracy of any symbol you encounter.

When in doubt – Go to early music concerts and listen to great recordings and videos. Read books, watch lectures, go to masterclasses, absorb the culture and sound of the music as best you can. Whenever I play a piece, for example Dowland, I will listen to as many reputable lute players as possible to get the style into my ears and, eventually, my hands.

Comparison – Dowland

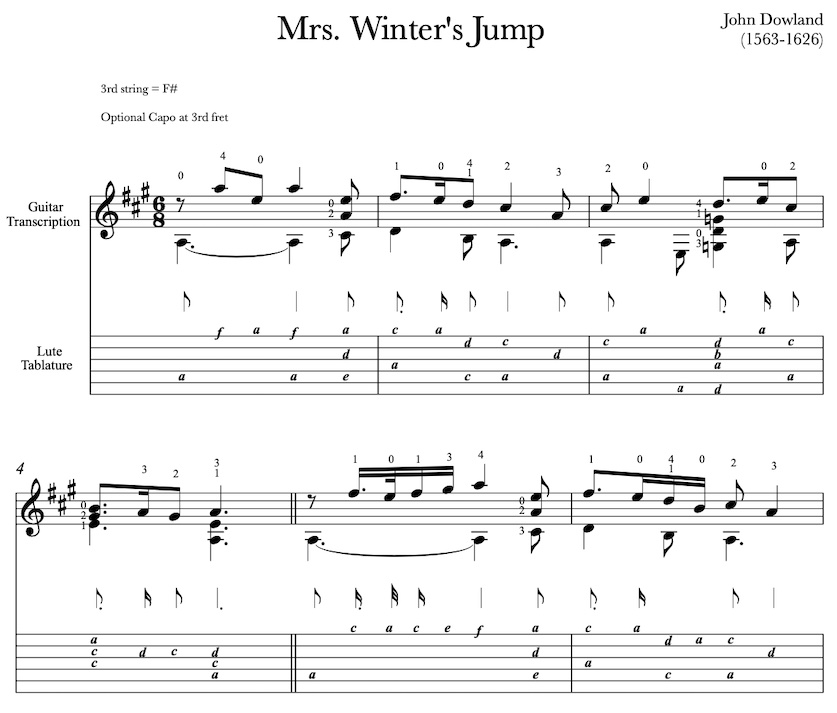

Below is an excerpt of a comparison score for Mrs Winter’s Jump by John Dowland (1563-1626). You can get the free and full pdf here. I included my very old video of it below to listen if needed.

Video by Brandon Acker

Here is a summary by Brandon Acker via his great YouTube channel. Visit is YouTube description to get the sheet music.

Further Resources

- Sites

- Beginners Lute Tutorial on LuteWeb – A great introduction to some resources and techniques as well as musical advice.

- The Lute Society – This English society has a number of resourses and helpful tips. Check out their tips and advice list which I’ve used on a number of occasions, the tuning charts in particular.

- The Lute Society of America – As above, a number of resources.

- Books

- A Tutor for the Renaissance Lute by Diana Poulton (Recommended) – For lute but valuable for guitarists. Learn to read lute tablature (French and Italian) and gain performance practice information. This book is an essential part of any library. Some previous experience or having a teacher will certainly help.

- A Guide to Playing Baroque Guitar by James Tyler (Recommended) – Very helpful resource for tuning and performance practices in Baroque guitar.

- Performance on Lute, Guitar, and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation (Cambridge) – A series of fascinating essays for the more advanced guitarist interested in performance practice. This is a tough read for beginners or even intermediates but a real eye opener otherwise.

- Performing Baroque Music on Classical Guitar by Peter Croton – This is more of a period resource book more than anything. But excellent from a period performance practice perspective.

- Continuo Playing on the Lute, Archlute and Theorbo: A Comprehensive Guide for Performers by Nigel North. Contains excellent info on continuo playing and realization but also a wealth of performance practice.

Check Back Soon

I’ll be updating this article to add more information and sections so check back often.

A very complex subject very well explained.

You appear to have covered everything important – concise and well written.

You must have spent a lot of time on this – thank you.

DB